Fact No. 36.

A constitution for a free Armenia was prepared in India in the 1770s-1780s.

One of the most interesting chapters in Armenian history is the Armenian community of India, and one of the most memorable pages of that chapter is the Madras Group – named for the major port city and trading centre in India’s south-eastern coast, today known as Chennai.

The Armenians of India were merchants that made their way east from Nor Jougha (New Julfa, the Armenian district of the Persian capital Isfahan) starting from the 17th century. They competed with the big European powers on their way to establishing colonies, and amassed great wealth in the process. At least a part of that wealth was put to use for larger, national causes, such as building churches and schools, and also, most notably, for printing.

The Armenians of Madras, led by Shahamir Shahamirian, are remembered as the source of the Nor Tetrak vor kochi Hordorak, “The New Pamphlet known as ‘Exhortations’”. This was a book that aimed at inspiring young Armenians to be informed and aware of their historical homeland and its state under foreign rule – even though that message was coming from a group of individuals, most of whom were at least a couple of generations removed from having set foot in Armenia at all.

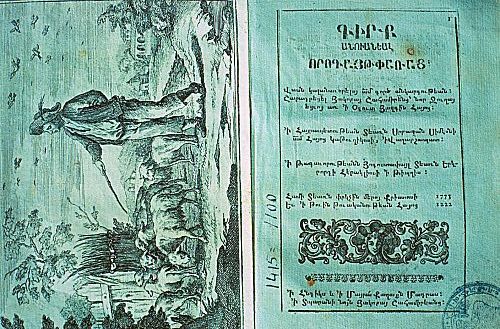

Further, Shahamirian’s printing house put together the Vorogayt Parats and Nshavak – “Snare of Glory” and “Target” – which were volumes that represent some of the very earliest modern constitutional political writing in the world. Although the print date on the cover for Vorogayt Parats says 1773, some scholars place it in the 1780s. The Vorogayt Parats lists out why representative governments are necessary and good, as opposed to monarchies, and why the Armenians, as a chosen people, must establish their own laws for themselves and abide by those alone.

The Nshavak is the document of laws itself, comprised of 521 articles in all. It has elements that are familiar to us in the 21st century, while also including clauses that we might consider out of place today. For example, while some equalities between men and women are guaranteed, men are given preferential treatment in acquiring inheritance and in some domestic rights. It also gives privileges to the Armenian Church, such as providing for representation from the clergy in legislative issues, while at the same time maintaining a degree of separation of the church from interfering in state matters. The Vorogayt Parats and Nshavak plan for a representative democracy, to be led by the House of Armenia (the parliament), which would be obliged to provide for orphans, including in terms of their education, while also looking after the sick, the elderly, the poor, and those with disabilities. A minority of the volume is of the classical constitutional style, actually, separating powers among offices. Most of the articles and clauses in there deal with regulations and day-to-day laws, including, for example, taxes on specific goods or codes of conduct for the military.

Some of the laws in the Nshavak would seem at the same time progressive and backward for us today, or even just plain funny. Article 381 prohibits anyone from hitting women, except as punishment as decided by a court – and except for her husband, who may deliver up to twelve lashes (but only upon soft flesh, without causing any lasting injury). Article 196 confiscates and gives to charity everything in hand from those who gamble during the day – but it would be all right to gamble while away long hours at night, as long as the winnings or losses don’t exceed two silver coins. Article 373 gives information on organising dinner parties, including seating arrangements and such advice as not inviting back people who get drunk or talk too much – adding that, if one has to invite them out of family obligations, then other invitees may excuse themselves from attending. The article following that obliges local authorities to hold dinner and dance parties four times a year. It lists all toasts in order, including how many gunshots are to be fired in honour of the subjects of the toasts (the Armenian people, high-ranking officials, a good harvest, love of our neighbours towards us, a pleasant time), to be followed by a light dinner, calm music and modest dancing. Article 374 ends by stipulating that one may stay up all night during the party, or one may leave for home whenever one wishes.

There’s a whole lot more in there. Even given all the variety of ideas and regulations, the Vorogayt Parats and the Nshavak represent revolutionary attitudes for their time. Not by coincidence, this was the same era as the American Revolution and the Articles of Confederation, and finally the US Constitution, which came into force in 1787. This book, it must be noted, beat the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of the French Revolution of 1789 and the Polish Constitution of 1791 to the printing press.

The Armenians of India were clearly in touch with modern, Enlightenment-era political thought coming out of Europe and, on top of that, they were ambitious enough to plan for how an independent Armenia could be run – an Armenia that would not appear on any maps until a century or two later.

References and Other Resources

1. Յակոբ Շահամիրեան. Գիրք Անուանեալ Որոգայթ Փառաց. Թիֆլիս, 1913

[Hakob Shahamirian. Book called Snare of Glory. Tbilisi, 1913]

digitised by Digilib.am

2. Simon Payaslian. The Political Economy of Human Rights in Armenia: Authoritarianism and Democracy in a Former Soviet Republic. I. B. Tauris, 2011, pp. 62-65

3. Hacikyan, Basmajian, Franchuk, Ouzounian. The Heritage of Armenian Literature, Vol. 3: From The Eighteenth Century To Modern Times. Wayne State University Press, 2005, pp. 160-167

4. David Zenian. “Dreams Come True: 18th Century Madras Armenians Envision an Independent Armenia”, AGBU News Magazine, July 1, 2001

5. This Week in Armenian History. “Birth of Shahamir Shahamirian – November 4, 1723”, November 4, 2013

Follow us on

Image Caption

The title page of the original publication of the Vorogayt Parats, including the motif of a shepherd tending to his flock.

Attribution and Source

By Gulbenkian Foundation archive [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Facts

Fact No. 100

…and the Armenian people continue to remember and to...

Fact No. 99

…as minorities in Turkey are often limited in their expression…

Fact No. 98

Armenians continue to live in Turkey…

Fact No. 97

The world’s longest aerial tramway opened in Armenia in 2010