Fact No. 57.

The Armenian alphabet has been used to write Turkish.

They are often referred to as the 36 soldiers – an army of letters that march the Armenian identity forth. The alphabet, after all, is the visible mark of a distinct language and culture. That the traditional story of the alphabet involves divine visions and the translation of the Bible only adds to its holy stature among the Armenian people.

That sense of ownership and uniqueness can therefore feel a little bit shattered when Armeno-Turkish comes to light. The Turkish language does not have an original alphabet of its own. Instead, a modified form of Arabic letters were used to write the Ottoman-era Turkish language, and among the changes that took place as the Republic of Turkey was established in the 1920s was language reform, including a whole new alphabet – a modified version of the Latin script (the same letters that English uses; check out our fact on one of the key architects of that reform).

Since the early 1700s, however, Turkish was already being written using another set of letters, the Armenian ones, right until as late as the mid-20th century, being published in places as far afield from the Ottoman Empire as Venice and Boston. Unsurprisingly, this was a practice of Turkish-speaking Armenians, either those who had lost their own language or those who found it far more advantageous to write Turkish in the Armenian script, as opposed to the far more complicated Arabic writing.

Indeed, the way that modern Turkish is written matches the Armenian set-up far more – with mostly separate letters for separate sounds, being written from left to right – rather than the cumbersome modifications, joint letters, and right-to-left writing that Arabic posed. There were even proposals to adopt the Armenian alphabet as the official writing of Ottoman Turkish in the late period of the empire, especially given that the Turkish elite was also familiar with that writing system.

More than just a second bunch of letters, Armeno-Turkish could be described as a cultural expression – an artifact of the Turkish-speaking Armenian, one that survived at least for a generation after the genocide. Among the earliest novels in Turkish was in Armeno-Turkish: Akabi Hikayesi (“Akabi’s Story”) by Hovsep Vartanian involved Armenian characters and Armenian themes, and Armenian letters, but the Turkish language. Many prayer books of the 19th century were published in Armeno-Turkish as well – most commonly by American missionary groups – so many Armenians would practice their Christian faith using the Turkish language to study the Bible or to pray. There were a number of Armeno-Turkish newspapers during that era, and even for decades after the genocide. Old, faded signs in Turkish using Armenian letters can still be found in the streets of Istanbul today. The last time an Armeno-Turkish book was published was in Buenos Aires in 1968.

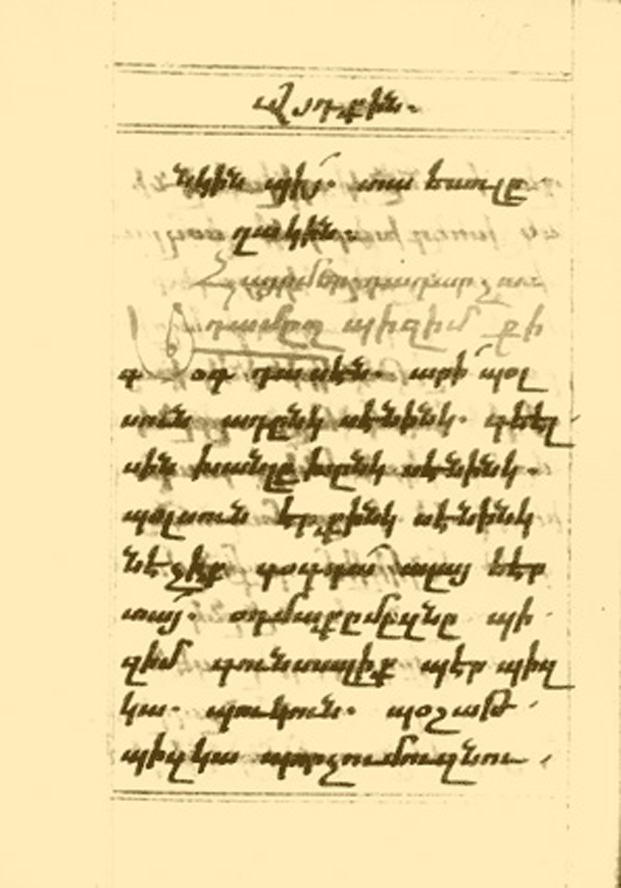

The Armenian alphabet was also used earlier, during the 17th century, for writing another Turkic language, Kipchak, which was used in what is today Ukraine and Poland. The Armenian communities there adopted that local language over some generations and put together written works unique for Kipchak in the Armenian script, also broadly under the influence of the Armenian language.

Both Armeno-Turkish and Armeno-Kipchak used the pronunciation of Western Armenian as the basis for writing, indicating the Diasporan path that was taken from the Ararat plain where Mesrop Mashtots lived and worked to Constantinople and points farther west and north.

References and Other Resources

1. St. Nersess Armenian Seminary. “Armeno-Turkish: Betrayal or Blessing?”, September 28, 2005

2. Armenian Research Center, University of Michigan-Dearborn and the Alex and Marie Manoogian Museum, Southfield, joint exhibit. Celebrating the Legacy of Five Centuries of Armenian-Language Book Printing, 1512-2012. University of Michigan-Dearborn, 2012

3. Rev. Andrew T. Pratt. “On the Armeno-Turkish Alphabet”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 8, 1866, pp. 374-376

4. Rouben Paul Adalian. Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Scarecrow Press, 2010, p. 264

5. Memorials: Written Monuments of Turkic Languages

6. Wikipedia: “Vartan Pasha”

Follow us on

Image Caption

The beginning of the Lord’s Prayer (“Our Father in Heaven …”) in Armeno-Kipchak, dating from the 17th century.

Attribution and Source

[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Facts

Fact No. 100

…and the Armenian people continue to remember and to...

Fact No. 99

…as minorities in Turkey are often limited in their expression…

Fact No. 98

Armenians continue to live in Turkey…

Fact No. 97

The world’s longest aerial tramway opened in Armenia in 2010