Fact No. 99.

…as minorities in Turkey are often limited in their expression by state policies…

The modern Republic of Turkey was established in the 1920s over the ashes of the Ottoman Empire – a multi-cultural land that had witnessed in its final years the purposeful decimation of part of its population to make way for a Turkish nation-state. The Armenian Genocide extended to Christians of other nationalities, namely Greeks and Syriac peoples. The Yezidi population was also targeted. But it was not just killing or deporting those millions which defined the new Turkey that took its place in Anatolia and Asia Minor, alongside Istanbul and its European environs. The regime led by Mustafa Kemal also implemented the policy of Turkification of all peoples that ended up within those new borders.

The Kurds rank highest among the identities that were suppressed in the decades that followed . (There is both irony and poignancy in the support by Kurdish individuals and groups to recognise the Armenian Genocide when one considers the role that many Kurds played in carrying it out.) Uprisings for Kurdish rights in the 1920s or ’30s were brutally suppressed, as was the later, long-lasting armed conflict of the 1980s and ’90s. The Kurdish problem in Turkey has in recent years found much more positive expression as the country has bit-by-bit moved away from its strict, Kemalist, secular state policies. Kurdish public figures are members of parliament in Turkey today, besides holding other offices – although armed resistance is not entirely ruled out. Domestic politics within Turkey tend to be unstable, and how fallouts from one election or scandal or military undertaking or another bear on the religious and ethnic minorities in the country remain to be seen each time. The situation of the Kurds, above all others, acts as a yardstick.

A second prominent group in Turkey are the Alevis, who comprise a religious minority, at times likened to Sufism, with origins in Shia Islam. The ethnic factor here – as Alevis include speakers of Kurdish, Turkish, or Arabic – is secondary to Alevis falling outside of the state-controlled Sunni Muslim religious bodies. They too have found themselves politically active and have faced violent repression as a result, particularly in the 1970s and 1990s. The Alevis were not party to the massacres and deportations of Armenians in 1915. On the contrary, numerous Armenians were protected by Alevis, and just as a number of Armenians ended up Turkified or Kurdified, many also joined Alevi families and took on that identity. In recent years, the process of reclaiming Armenian heritage has extended to Alevis in Turkey as well, in particular in the region of Dersim or Tunceli, where there has been established a “Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Society”. There is also an account of the Alevi religion being rooted in pagan Armenian sects . (Our previous fact also discussed “crypto-Armenians” or “hidden Armenians” in the Turkish interior.)

A number of other minorities exist in Turkey today, such as peoples of Caucasian or Balkan descent, or of other Turkic, Central Asian, or Middle Eastern origins, for example the Laz, Arabs, or the Roma (Gypsies), to name just a few. Religious groups that fall outside the mainstream include Yezidis, Baha’ is, and Protestant Christians. Atheism is also not uncommon, following the secular line that has been in place for so many years.

The most distinct minorities remain the three that were named in the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, according to which Turkey was obliged to maintain their rights – an imperfect record at best for ninety years and more. The Armenians, Greeks, and Jews have their mainstay in Istanbul, the most cosmopolitan city in Turkey today. Turkifying these three proved to be a lost cause, so their community organisations – churches, schools, newspapers – have had to make do with governmental supervision. It is true, however, that since the AK Party has come to power in 2002, more freedoms have been granted in terms of cultural expression and public dialogue. Tensions still remain in that regard, however, given the outcry that followed, for example, the revelation in 2013 of the encoding of Turkish citizens on government records to mark their ethno-national background.

References and Other Resources

1. Uğur Ümit Üngör. The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. Oxford University Press, 2012

2. Nigar Karimova, Edward Deverell. Minorities in Turkey. The Swedish Institute of International Affairs, 2001

3. Minority Rights Group International. World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples: Turkey

4. Luke Montgomery. “Doomed to Disappear? Religious minorities in Turkey”, The Washington Times Communities, September 4, 2012

5. Dorian Jones. “Tensions Rise Between Turkey’s Government, Alevi Minority”, Voice of America, October 22, 2013

6. Raffi Bedrosyan. “Dersim Armenians Return to their Roots”, Keghart.com, March 3, 2015

7. Varak Ketsemanian. “‘Les Fils du Soleil’: An Inquiry into the Common History of the Armenians and Alevis of Dersim”, The Armenian Weekly, September 15, 2014

8. “Turkish Interior Ministry confirms ‘race codes’ for minorities”, Hürriyet Daily News, August 2, 2013

9. Johan Bodin, Achren Verdian, “Turkey’s hidden Armenians search for stolen identity”, France 24, April 17, 2015

10. Wikipedia: “Minorities in Turkey”

11. Wikipedia: “Ahmet Ali Çelikten”

12. Wikipedia: “Slavery in the Ottoman Empire”

Follow us on

Image Caption

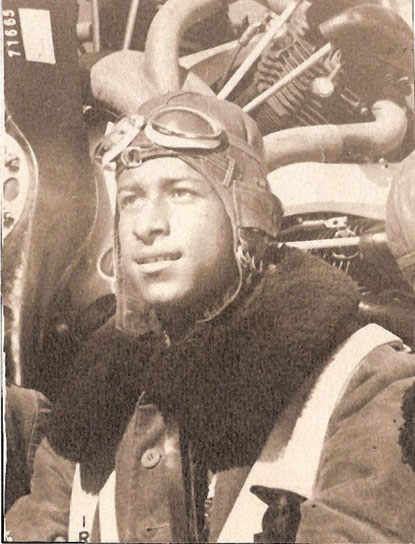

Ahmet Ali Çelikten (1883-1969), a representative of the African Turkish minority, the ancestors of whom were slaves in the Ottoman Empire; he served as a pilot in the Ottoman Air Force and later in the Turkish military.

Attribution and Source

By NA (NTVMSNBC) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Facts

Fact No. 100

…and the Armenian people continue to remember and to...

Fact No. 99

…as minorities in Turkey are often limited in their expression…

Fact No. 98

Armenians continue to live in Turkey…

Fact No. 97

The world’s longest aerial tramway opened in Armenia in 2010