Fact No. 51.

Armenian was one of the first languages into which the Bible was translated.

It is hard to the dispute that the Bible is one of the most widely-published, widely-distributed, and widely-translated written works in all of history. Whereas the Old Testament was written originally in Hebrew, as well as in parts in Aramaic, Greek was the most used language of the Near East by the time the New Testament came around. Meanwhile, the Old Testament had also itself been rendered into Greek by around 132 BC, a version that has since come to be known as the Septuagint (from the Latin for “seventy”, citing the number of translators needed). Diaspora Jews had, during their exile in Babylon centuries earlier, brought about versions of the scripture in Aramaic as well, known as Targums – the word being ultimately the root of the Armenian word for “translate” (“targmanel” or “tarkmanel”).

After Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, one would expect Latin to be the next major language on the list. Indeed, the Vulgate – the Latin translation made by Jerome in the 4th-5th century AD – dominated European life for a thousand years and more. Meanwhile, Syriac (related to Aramaic) became and continues to be the working liturgical language of many Christians of the Near East. There are other very early translation records as well, such as a Gothic Bible prepared in what is Bulgaria today around the year 350 AD.

Armenia officially adopted Christianity early in the 4th century, traditionally in 301 AD. But it took another hundred years before the problem of rendering the Bible into the Armenian language was taken up. Armenian chroniclers maintain that the lack of the holy scripture in the local language was an obstacle to missionary work. In fact, the main motivation behind the creation of the Armenian alphabet itself by Mesrop Mashtots lay in having an Armenian Bible, which can be referred to as “the Holy Book” in the language (“Sourp Kirk” in Western Armenian pronunciation, or “Sourp Girk” in Eastern), but is more often called “Astvatsashounch” (Eastern) or “Asdvadzashounch ” (Western) – “Inspired of God” being one way to interpret that in English.

There is evidence of both Syriac and Greek influence in the translation of the Bible completed by 436 AD into what we now call Classical Armenian, Grabar (or Krapar). It is often marked by scholars as “The Queen of the Versions” for its style and literal rendition of the original. The very first words written in Armenian, by tradition, come from the Book of Proverbs of the Old Testament: “To know wisdom and instruction; to perceive the words of understanding” (as the King James Version in English has it). The choice is not lost in the celebration of the Holy Translators, whose Armenian Church feast day in October is used to commemorate learning and at times to usher in the new school year, depending on a given Diaspora community’s location. The Armenians may be the only people in the world who venerate translators in that way.

Although there are other relatively early versions of the Bible – such as those among Ethiopians, Copts, and Georgians, or the Old Church Slavonic translation – and bits and pieces were made into some local languages on occasion, it was another thousand years or so before the major languages that we think of today got to have their own translations of the Bible.

Translations into modern versions of Armenian have also been made in the 19th and 20th centuries, although the Classical Armenian language still tends to be used during church services.

References and Other Resources

1. Robert B. Waltz. “Versions of the New Testament”, The Encyclopedia of New Testament Textual Criticism

2. W. St. Clair Tisdall. “Armenian Versions, of the Bible”, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Online

3. Wikipedia: “Bible translations”

4. Wikipedia: “Bible translations into Armenian”

Follow us on

Image Caption

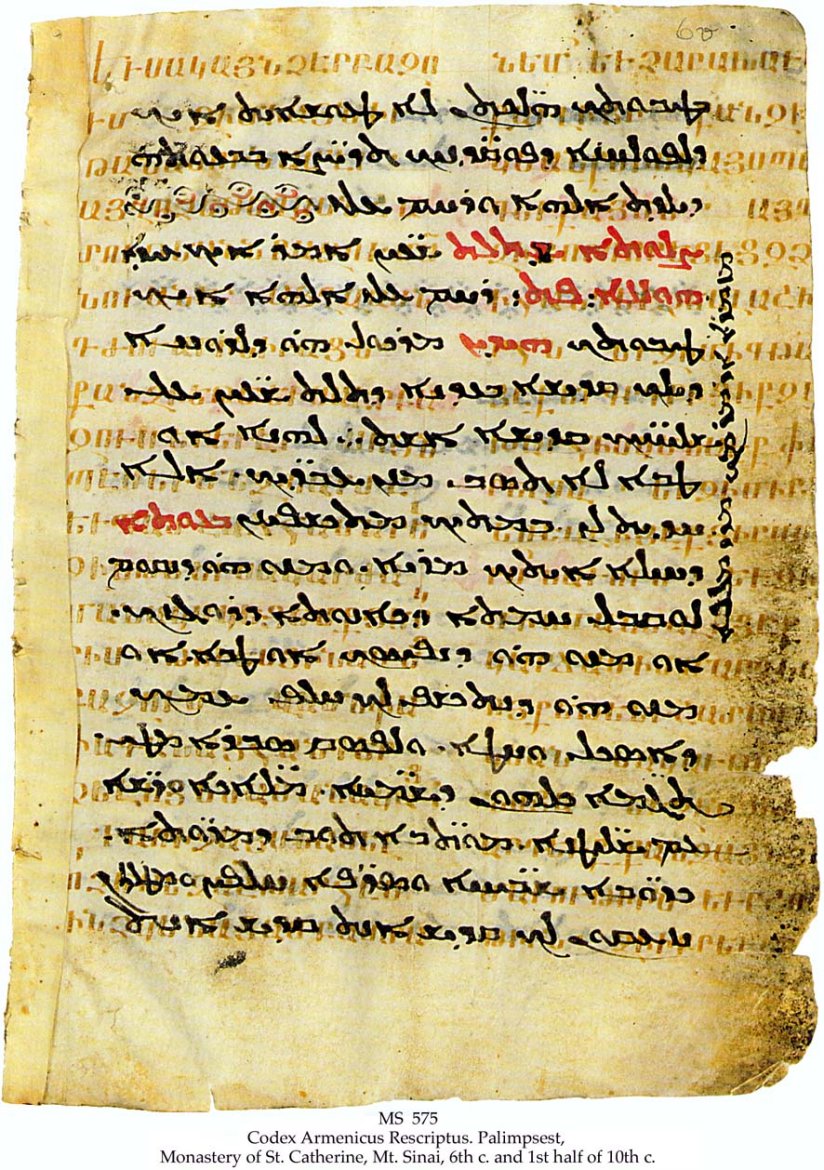

A palimpsest, or a manuscript written over with some other text – a not uncommon practice during times when paper was scarce – with 10th-century Syriac prayers over 6th century Armenian religious writing, from St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai in Egypt today.

Attribution and Source

[Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Facts

Fact No. 100

…and the Armenian people continue to remember and to...

Fact No. 99

…as minorities in Turkey are often limited in their expression…

Fact No. 98

Armenians continue to live in Turkey…

Fact No. 97

The world’s longest aerial tramway opened in Armenia in 2010